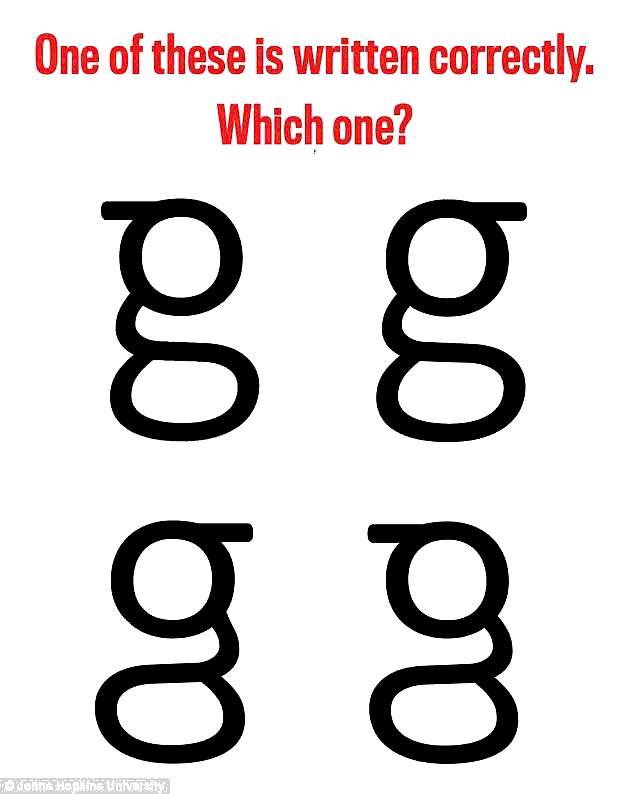

If you know which is the right G then you’re cleverer than 72% of the population

Scientists have worked out that most people don’t know which is the right letter G despite seeing it every day.

25 people were tested and only 7 got it right.

Probably as few write Gs like this in and this writer could only remember the correct one by thinking about the Guardian logo.

The correct answer is…. We’ll make you scroll for it so you don’t accidentally read it.

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

KEEP SCROLLING…

The correct one is top right.

Read the full study if that’s your thing.

Knowledge of letter shapes is central to reading. In experiments focusing primarily on a single letter shape—the “looptail” lowercase print G—we found surprising gaps in skilled readers’ knowledge. In Experiment 1 most participants failed to recall the existence of looptail g when asked if G has two lowercase print forms, and almost none were able to write looptail g accurately. In Experiment 2 participants searched for Gs in text with multiple looptail gs. Asked immediately thereafter to write the g form they had seen, half the participants produced an “opentail” g (the typical handwritten form), and only one wrote looptail g accurately. In Experiment 3 participants performed poorly in discriminating looptail g from distractors with important features mislocated or misoriented. These results have implications for understanding types of knowledge about letters, and how this knowledge is acquired. For example, our findings speak to hypotheses concerning the role of writing in learning letter shapes. More generally, our findings raise questions about the conditions under which massive exposure does, and does not, yield detailed, accurate, accessible knowledge. In this context we relate our findings to studies showing poor knowledge or memory for various types of stimuli despite extensive exposure.